FILM NOIR

‘I have done many pictures which I suppose are film noir. And I can see the roots of that in Citizen Kane… but I couldn’t define it for you, then or now.’ Robert Wise, director of noir classics like Born to Kill (1947) and The Set-Up (1949), was wary of a definition, perhaps because film noir encompasses many genres from private eye thrillers – like perhaps the first noir, Huston’s ‘depraved’ (LA Times) The Maltese Falcon, 1941 – to erotic love stories (Gilda, 1946). The term (meaning ‘dark film’) is an invention of a French critic, Nino Frank, in 1946, but not until the 1970s was it popularised. That it was a French expression is no coincidence. France had been starved of American movies during WW2 so when in one year – 1946 – they saw The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity (1944) and Laura (1944) they perceived a pattern that eluded US critics. France also treated film as an art form, not just commercial entertainment. They intellectualised film, especially in the journal Cahiers du Cinéma whose inaugural issue (1951) featured a still from Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) on the cover.

‘I have done many pictures which I suppose are film noir. And I can see the roots of that in Citizen Kane… but I couldn’t define it for you, then or now.’ Robert Wise, director of noir classics like Born to Kill (1947) and The Set-Up (1949), was wary of a definition, perhaps because film noir encompasses many genres from private eye thrillers – like perhaps the first noir, Huston’s ‘depraved’ (LA Times) The Maltese Falcon, 1941 – to erotic love stories (Gilda, 1946). The term (meaning ‘dark film’) is an invention of a French critic, Nino Frank, in 1946, but not until the 1970s was it popularised. That it was a French expression is no coincidence. France had been starved of American movies during WW2 so when in one year – 1946 – they saw The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity (1944) and Laura (1944) they perceived a pattern that eluded US critics. France also treated film as an art form, not just commercial entertainment. They intellectualised film, especially in the journal Cahiers du Cinéma whose inaugural issue (1951) featured a still from Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) on the cover.

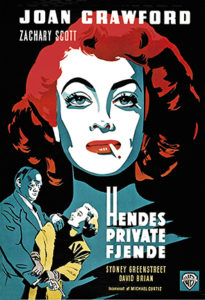

VIOLENCE

Film noirs are dark in tone and theme. Sometimes literally dark, with neon flashing above wet sidewalks at night. If most were monochrome, with heavy shadows inspired by German Expressionism, some were colour like Leave Her to Heaven (1945) and Niagara (1953 – with Monroe); these are noir movies despite Technicolor – noir in their cynicism (itself the product of WW2) and violence. ‘Incoherent brutality’ runs through the genre, as the first French book on noir (1955) called it. In The Set-Up (1949) Robert Ryan is beaten to death in an alley; in Kiss of Death (1947) Richard Widmark giggles with glee as he pushes an old lady down a flight of stairs; in The Big Heat (1953) Lee Marvin throws boiling coffee at Gloria Grahame’s face – who later returns the favour. Film noirs feature flashbacks, offscreen narration (in Sunset Boulevard by a dead man), convoluted plots: in The Big Sleep (1946) so convoluted that it was unintelligible to both actors and public, particularly after a scene in which Humphrey Bogart explains plot twists was cut. In noir you find heroes and heels, conspiracy, crime, betrayal, seedy diners, swanky clubs, tough women, corrupt cops, liquor, sex (though expurgated by the censor)… It may be an oversimplification that all you need for a noir film is a gun, a girl and a car – to misquote Jean-Luc Goddard – but it helps. Goddard’s Breathless (1960) is a homage to noir B movies.

HARD-BOILED FICTION

Hard-boiled American fiction by Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Hemmingway is the inspiration. A line from a Chandler short story (1950) sums up the noir hero: ‘Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.’ And this Chandleresque narration from Philip Marlowe in Murder My Sweet (1944) sums up the style: ‘She was a charming middle-aged lady with a face like a bucket of mud. I gave her a drink. She was a gal who’d take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle.’ Marlowe was the quintessential private dick. Of his gun he said – ‘That’s just part of my clothes. I hardly ever shoot anybody with it.’

Hard-boiled American fiction by Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Hemmingway is the inspiration. A line from a Chandler short story (1950) sums up the noir hero: ‘Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.’ And this Chandleresque narration from Philip Marlowe in Murder My Sweet (1944) sums up the style: ‘She was a charming middle-aged lady with a face like a bucket of mud. I gave her a drink. She was a gal who’d take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle.’ Marlowe was the quintessential private dick. Of his gun he said – ‘That’s just part of my clothes. I hardly ever shoot anybody with it.’

WELLES’S INFLUENCE

The noir heyday was the 40s and 50s, culminating in Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958). It is fitting that Welles should span its extent – Citizen Kane (1941) isn’t noir in theme but its style, its lighting and editing and structure, influenced the noir generation of directors and cinematographers (as did Weegee’s grim flashlit street photos and Edward Hopper’s lonely streetscapes). Much of the noir effect was necessity. WW2 forced studios to limit studio lighting and stages. Location shooting was the answer. Colour stock was restricted, but black and white photography could reflect drama, menace and alienation. The dark wastes of the screen were filled by white cigarette smoke.

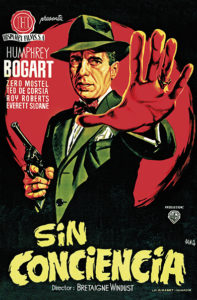

BOGEY

The man most associated with noir is Humphrey Bogart. He once summed up his laconic style: ‘If a guy points a gun at you, the audience knows you’re afraid. You don’t have to make faces.’ Mrs Bogart, Lauren Bacall, is the woman. Scenes in The Big Sleep were reshot – like the famous exchange below – after audiences loved her ‘insolence’ in To Have and Have Not (1944): Vivian So you’re a private detective. I didn’t know they existed, except in books. Or else they were greasy little men snooping around hotel corridors. My, you’re a mess, aren’t you? Marlowe I’m not very tall either. Next time, I’ll come on stilts, wear a white tie and carry a tennis racket.