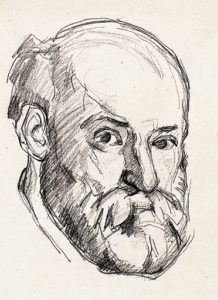

PAUL CÉZANNE (1839-1906): Father of Modern Art

‘I point the way. Others will come after.’ The Post-Impressionist Cézanne was, according to Picasso, ‘the father of us all – my one and only master!’ Braque’s revolutionary Cubist painting Houses at l’Estaque (1908) owes everything to Cézanne. The critic who coined the term ‘Cubism’ was being rude when he wrote that Braque ‘reduced everything, places and figures and houses, to geometric schemes, to cubes.’ But it was essentially what Cézanne invented: the simplification of natural forms to their geometric essentials, ‘treating nature in terms of the cylinder, sphere and cone’. He was obsessed with the truth of perception. ‘The truth is in nature, and I shall prove it.’

PERSPECTIVE

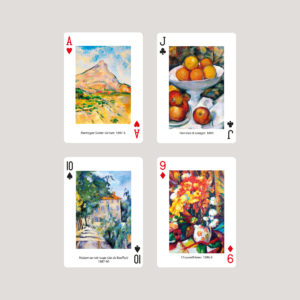

It led him to explore binocular vision graphically, to abandon single-point perspective in favour of different points of view (of nature or objects) in a particular work (partly influenced by the stereoscopic fad of the day). It made painting on a flat surface truer to the experience of vision, which is a series of successive images, a constantly shifting perspective. His Still Life with Basket of Apples (1890-94) offers different views of objects. The tabletop and the basket are seen from two different angles; each apple is painted individually so cannot be integrated into one point of view. Perspectival sense is immaterial; Cézanne was more interested in relating objects to each other.

But for all the rigour of his scientific approach, of recreating the classical composition of Poussin after nature (‘what art needs is a Poussin made over according to nature’), his painting was above all emotional – for ‘an art which isn’t based on feeling isn’t an art at all.’

But for all the rigour of his scientific approach, of recreating the classical composition of Poussin after nature (‘what art needs is a Poussin made over according to nature’), his painting was above all emotional – for ‘an art which isn’t based on feeling isn’t an art at all.’

Cézanne would sometimes take years to complete a picture, returning to it endlessly. A single stroke (a palette knife was often preferred) could take hours because each needed to contain ‘the air, the light, the object, the composition, the character, the outline, and the style’. A still life might mean 100 sessions (so his apples were sometimes artificial). He believed he was capturing a moment in time – once passed, it was lost.

PISSARRO’S INFLUENCE

If he was a perfectionist, he was also disagreeable and grumpy. Born to a wealthy family in Provence (father was a banker) he went to school with Emile Zola, who later encouraged him to move to Paris to study art (overcoming his father’s opposition), where he was drawn to Delacroix and the realists Courbet and Manet. His early works were dark in tone but after he was befriended by Camille Pissarro, his palette became lighter, he began working en plein air and learnt the new Impressionist technique for rendering outdoor light. He exhibited with the Impressionists but a critic called him ‘a madman who paints in delirium tremens’.

It was ‘the humble and colossal Pissarro’ who gave the depressive and withdrawn Provençal confidence. The admiration was reciprocated. If Cézanne referred to ‘the great Pissarro, my master’ and ‘mon bon Dieu, Pissarro’, Pissarro acknowledged that ‘he was influenced by me and I by him.’ Cézanne had a son (1872) by his mistress, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, whom he later married. She’d been his model. He kept all this quiet from his father in case he was cut off financially. The marriage was unhappy. ‘My wife only cares for Switzerland and lemonade’, whined Cézanne. But he admitted that ‘the world doesn’t understand me and I don’t understand the world, that’s why I’ve withdrawn from it.’ Such an unclubbable fellow (who couldn’t ‘bear to be touched’ and whose table manners were disgusting) might not be the easiest of husbands. He disinherited her after they split. The allowance she received from her son (after her ex’s death) she gambled away. At the end of his life, a Paris dealer exhibited his work; his genius was at last appreciated. Young artists travelled to Aix, where he’d returned, to pay homage.

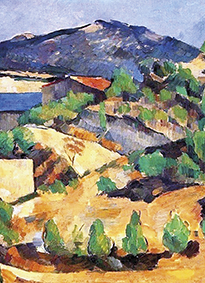

MONT SAINTE-VICTOIRE

I find his paintings of the limestone Mont Sainte-Victoire, in his native Provence, his most sublime creations. Forget the science of their creation (horizontal lines to create breadth, vertical ones to suggest depth), just luxuriate in the landscape, revel in the colour, the heat. ‘Our native soil,’ said Cézanne, ‘is so vibrant, so reverberant with light that your eyes…are enchanted. The sun is so startling that it makes it look as if objects are cast not just in black or white, but in blue, red, brown, purple.’ And he added: ‘I love the contours of my countryside’. No wonder. But Cézanne was never happy, never satisfied. ‘Painting is damned difficult – you always think you’ve got it, but you haven’t.’ He never gave up trying. ‘I’ve sworn to die painting’, he said. In 1906, Cézanne was caught in a storm while working in the field and died of pneumonia. He was true to his word.

I find his paintings of the limestone Mont Sainte-Victoire, in his native Provence, his most sublime creations. Forget the science of their creation (horizontal lines to create breadth, vertical ones to suggest depth), just luxuriate in the landscape, revel in the colour, the heat. ‘Our native soil,’ said Cézanne, ‘is so vibrant, so reverberant with light that your eyes…are enchanted. The sun is so startling that it makes it look as if objects are cast not just in black or white, but in blue, red, brown, purple.’ And he added: ‘I love the contours of my countryside’. No wonder. But Cézanne was never happy, never satisfied. ‘Painting is damned difficult – you always think you’ve got it, but you haven’t.’ He never gave up trying. ‘I’ve sworn to die painting’, he said. In 1906, Cézanne was caught in a storm while working in the field and died of pneumonia. He was true to his word.