Mary Cassatt: American Impressionist

‘I took leave of conventional art. I began to live.’

So said Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) about her invitation in 1877 to join the Impressionists, the ‘true masters’. She overcame several obstacles to become an artist in Paris (‘the capital of the nineteenth century’) where she settled in 1874. She was a woman, daughter of a stockbroker; and foreign. She was born in Pennsylvania. Her parents were rather grand. Society girls did not paint, and most decidedly did not draw nude models.

But she was determined, and in 1861 enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. However, there was a hitch. Artists needed to study the old masters and only Europe offered public collections of great art, like the Louvre. Her father, although disappointed by her rejection of a ‘proper’ life as wife and mother, let her go to Paris provided she enrolled in the staid academic studio of a painter called Charles Chaplin. She did; but hated it. ‘One does not need lessons. Museums are sufficient.’ She took time off to study the Mannerists in Parma, Rubens in Antwerp and Velázquez in Madrid and Seville, but soon became entranced by the French realists: Courbet, Manet and particularly Degas – whose love of drawing, and of painting people, she shared. Degas’ pastel drawings, spotted in a dealer’s window, ‘changed my life,’ she said. ‘I saw art then as I wanted to see it.’ Despite the Paris Salon having accepted her early paintings (from 1872), she was rejected in 1877 and was bitter. One critic commented that ‘she snubs the Salon pictures we used to revere.’

But in 1877, Degas – now a friend and mentor – asked her to exhibit at the 4th Impressionist exhibition. Degas had seen a Cassatt painting in the Salon and thought – ‘This is someone who feels the way I do.’ Degas was a grumpy bourgeois misogynist. He commented of Cassatt’s brilliant Japanese-inspired prints: ‘I don’t believe a woman can draw that well.’ With rare generosity, he said to her: ‘Most women paint as though they are trimming hats. Not you.’ Degas taught her a love of form, dislike of pointless detail and how to use bright, prismatic colour.

Were they lovers? No. Van Gogh thought that Degas lived ‘like some petty lawyer and doesn’t like women’ – his virility went into his painting. But Cassatt would have loved a family. ‘There’s only one thing in life for a woman; it’s to be a mother.’ She regretted that ‘a woman artist must be capable of making primary sacrifices.’ Yet she also relished her calling. ‘I am independent! I can live alone and I love to work… Can you offer me anything to compare to that joy for an artist?’

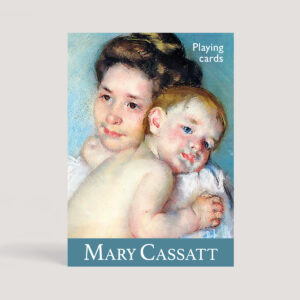

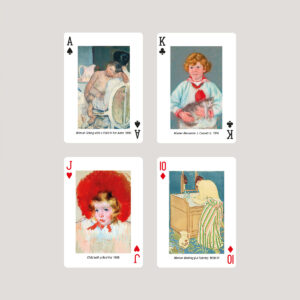

If her lustre derives from her technical skill, and her mastery of line and colour, her fame rests (unfairly perhaps) on her portraits of children, and mothers cuddling babies. They reveal flesh tones that owe much to Rubens and Renoir, although the approach is wholly American. ‘I am American,’ she said, ‘clearly and frankly American.’ Cassatt has a freshness, a directness, that is transatlantic, with none of Degas’ cynicism or Renoir’s Gallic abandon.

If her lustre derives from her technical skill, and her mastery of line and colour, her fame rests (unfairly perhaps) on her portraits of children, and mothers cuddling babies. They reveal flesh tones that owe much to Rubens and Renoir, although the approach is wholly American. ‘I am American,’ she said, ‘clearly and frankly American.’ Cassatt has a freshness, a directness, that is transatlantic, with none of Degas’ cynicism or Renoir’s Gallic abandon.

Babies wriggle, they cannot hold a pose; her portraits are testament to her visual memory and drawing skills. She was the opposite of the temperamental artist. In her pictures of women, Cassatt portrays cultured, animated figures at the theatre or caught in mid-conversation. She also reveals complex relationships expressed through gestures and space.

Successful in Paris, she failed to sell in America. During Cassatt’s visit to Philadelphia in 1898, newspapers mentioned nothing of her fame in Paris. One wrote: ‘Mary Cassatt, sister of Mr. Cassatt, President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, owns the smallest Pekingese dog in the world.’ Mary was ‘very much disappointed that my compatriots have so little liking for any of my work.’ But she adopted a new role. She became art advisor and consultant to the rich, particularly (the fellow suffragist) Louisine Havemeyer, and introduced Impressionist art to collectors. Late in life her eyesight failed. Her last works (she stopped painting entirely in her last decade) are evidence of decline. After a disastrous trip to Egypt in 1911 (in which her brother died) she suffered a breakdown.

An American critic once wrote of ‘the odd contrast between the boldness of Cassatt’s style and the world of perpetual afternoon tea it serves to record… a Jamesian world of well-bred ladies delighting in their well-behaved children.’ He ignores the irony of her social vignettes, and misses something unique among Impressionists: individual expression. In France, until recently, she was remembered as a painter of babies. But there is nothing parochial or trite in these deeply personal, feminine homages to motherhood. They inspire. ‘I love to paint children,’ she wrote. ‘They are so natural and truthful.’ As natural and truthful as her painting.