‘Mondrian realizes the importance of line. The line has almost become a work of art in itself… Each superfluous line, each wrongly placed line, any colour placed without veneration or care, can spoil everything – that is, the spiritual.’ Theo van Doesburg (1915)

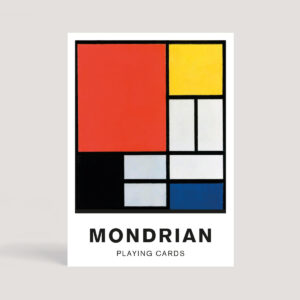

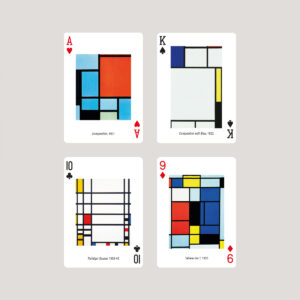

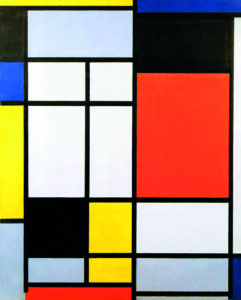

The art of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) is precise, austere even. ‘Curves are so emotional,’ he said. He wanted ‘nothing specific, nothing human’ in his art. The compositions of his mature period use only black, white and primary colours, based solely on the rectangle and square, the vertical and horizontal, representing the essential opposing forces: positive and negative, dynamic and static… and (in his view) masculine and feminine. Around 1912, trees in his painting were bent and reduced into the black lines and angles that would soon become grids. Their chaos became anathema. Spotting one through the window of a downtown New York collector in 1941, he shuddered: ‘You didn’t tell me you lived in the country.’ On the train to London (where he lived 1938-40) did he enjoy the Kent countryside? No. Only the verticals of the telegraph poles.

The art of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) is precise, austere even. ‘Curves are so emotional,’ he said. He wanted ‘nothing specific, nothing human’ in his art. The compositions of his mature period use only black, white and primary colours, based solely on the rectangle and square, the vertical and horizontal, representing the essential opposing forces: positive and negative, dynamic and static… and (in his view) masculine and feminine. Around 1912, trees in his painting were bent and reduced into the black lines and angles that would soon become grids. Their chaos became anathema. Spotting one through the window of a downtown New York collector in 1941, he shuddered: ‘You didn’t tell me you lived in the country.’ On the train to London (where he lived 1938-40) did he enjoy the Kent countryside? No. Only the verticals of the telegraph poles.

If his art was serious, he wasn’t some ascetic monk. He loved nightlife and women. It was where his money went. And he loved dancing. He was known as ‘The Dancing Madonna’ in Holland. But women hated to dance with Mondrian because he practised his rigid geometry on the dance floor. He disliked the sentimentality of the waltz and the tango, preferring the 90-degree angles of the Charleston and the foxtrot. He nearly married in 1912, but was relieved he didn’t. ‘I have always lived for art.’

Mondrian’s art derives (appropriately) in a straight line through Cézanne, Picasso and the Cubists (he met Picasso in Paris in 1912) with their belief that all natural shapes can be reduced to the cube, the cone and the sphere… ‘I continued my research by abstracting the form and purifying the colour more and more.’ Whereas Cubism plays with simple shapes in a complex arena, Mondrian stressed the flatness of the painting surface, distilling figures to the elemental and eliminating perspective, the illusion of depth.

Van Doesburg and Mondrian founded a movement, Der Stijl (‘The Style’), in 1917 – dedicated to the ‘absolute devaluation of tradition’. Born out of the destructive confusion of the Great War, it sought the simplicity and order of pure abstraction (‘reality is opposed to the spiritual’). Neo-Plasticism, his ‘new art’, eroded the distinctions between art, architecture and design, and aimed to harness the mysticism of nature through revealing its essence (‘the colours of nature cannot be reproduced on canvas…painting had to find a new way to express the beauty of nature’). By using basic forms and colours, he wanted modern art to transcend cultural divides, foment harmony. If his utopian purpose was unachievable, his use of asymmetrical balance and his simplified pictorial vocabulary influenced the Bauhaus, and modern art and design today (as in Yves Saint Laurent’s Mondrian sack dress of 1965). He saw his art as didactic, but not imperious – ‘nothing is stable and no certainties are possible’ – and would add that ‘the position of the artist is humble. He is essentially a channel.’

Piet Mondrian (born Pieter Mondriaan) grew up in a Calvinist home in central Holland. His father, a local headmaster, was a keen amateur artist who taught his son to draw, and in 1892 sent him to art college in Amsterdam. His early work, both landscape and portraits, are vividly coloured and sometimes pointillist. For Mondrian, art and philosophy were intertwined; in 1909 he joined the Theosophical Society (based on Buddhism). From 1919-38 he worked in Paris (before London and New York). Always insecure financially, he nevertheless became a sort of modernist god, compared (by the Brooklyn Museum) with Rembrandt and van Gogh.

‘Always further,’ is how Mondrian termed his drive to transform his art. He did not stand still. Working within his strict grid were the diamond-shaped ‘lozenge’ paintings (from 1918), which introduced the diagonal and expressed a more dynamic rhythm and tension. The culmination of Mondrian’s pursuit of conveying order out of jumble is Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-3), where his black grid has been replaced by strips of colour, made out of tape, interspersed with blocks of solid colour. It is inspired by the vitality of New York and the tempo of jazz, a music and rhythm he sought to echo in his painting.

‘Always further,’ is how Mondrian termed his drive to transform his art. He did not stand still. Working within his strict grid were the diamond-shaped ‘lozenge’ paintings (from 1918), which introduced the diagonal and expressed a more dynamic rhythm and tension. The culmination of Mondrian’s pursuit of conveying order out of jumble is Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-3), where his black grid has been replaced by strips of colour, made out of tape, interspersed with blocks of solid colour. It is inspired by the vitality of New York and the tempo of jazz, a music and rhythm he sought to echo in his painting.

A similar painting, New York City 1 (1941), was hung on a museum wall in Düsseldorf for 50 years. Upside down. Mondrian, who liked a giggle and a bit of grog, might have enjoyed that.