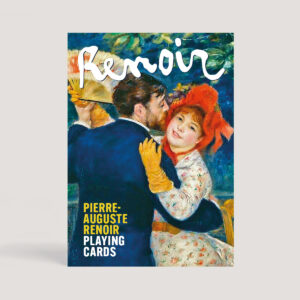

‘To my mind, a picture should be something pleasant, cheerful, and pretty, yes pretty! There are too many unpleasant things in life as it is, without creating still more of them.’ Pierre-Auguste Renoir

To enjoy RENOIR you don’t need to know about the science or artifice behind those dappled scenes of bathers or revellers. They were painted for his pleasure, and yours. Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) is the essence of Renoir. It combines figures – portraits of his friends – still-life, and landscape in one work. Men and women relax oblivious of social distinction. In the foreground is a young woman playing with a toy dog. The original model annoyed Renoir so he brought in the young Aline Charigot. In 1890 they married. The picture is carefully composed, using linear perspective. But let us not overanalyse. Renoir explained Impressionism simply: ‘One morning, one of us ran out of the black, it was the birth of Impressionism.’ But added: ‘Art is about emotion; if art needs to be explained it is no longer art.’

To enjoy RENOIR you don’t need to know about the science or artifice behind those dappled scenes of bathers or revellers. They were painted for his pleasure, and yours. Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) is the essence of Renoir. It combines figures – portraits of his friends – still-life, and landscape in one work. Men and women relax oblivious of social distinction. In the foreground is a young woman playing with a toy dog. The original model annoyed Renoir so he brought in the young Aline Charigot. In 1890 they married. The picture is carefully composed, using linear perspective. But let us not overanalyse. Renoir explained Impressionism simply: ‘One morning, one of us ran out of the black, it was the birth of Impressionism.’ But added: ‘Art is about emotion; if art needs to be explained it is no longer art.’

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born in 1841 in Limoges. His father was a tailor and his mother a dressmaker. Financial woes forced him to leave school and work as a painter in a porcelain factory. The young Renoir moved to Paris and entered the École des Beaux-Arts, later joining the studio of Charles Gleyre. Renoir was broke and often couldn’t afford paint, but he lived close to the Louvre where he could study the Old Masters.

In 1869 he sketched with Monet beside the Seine, en plein air – painting outside was made easier by new portable easels and paints coming in lead tubes. Here they could observe colours away from the artificial setting of the studio. Monet once said: ‘I have never had a studio, and I do not understand shutting oneself up in a room. To draw, yes; to paint, no.’ They developed the techniques, practices and theories (based on the science of complementary colours) that became Impressionism (in part made possible by new flat brushes, allowing loose, broken brushstrokes).

Renoir, Monet and their circle found their work rejected by the Salon so staged their own show. Renoir displayed six paintings in the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874 (‘insurrectionist art’ a critic commented). It was the exhibition where Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) inspired the movement’s name. Renoir included La Loge (1874), showing a couple in a theatre box (in fact a model – known as ‘fish-face’ – and Renoir’s brother). It is a subtle symphony in black and white. But one journal complained that the lady’s vulgar ‘overdressed’ appearance made her look like a tart. The Impressionists gained a reputation for louche subjects.

Renoir was a chameleon, his painting often aping – for short periods – an artist he admired, be it Monet, Sisley or Cézanne. His early influences were Courbet and Rubens (for his exuberant fleshiness). And Delacroix. In 1881, he followed in Delacroix’s footsteps and went to Algeria. Thence to Madrid (for Velázquez) and Italy (for Raphael, Titian and Veronese) and Pompeii. He wanted to learn from the ‘grandeur and simplicity of the ancient painters.’

When Renoir returned he adopted a more classical, studio-based approach – also influenced by Ingres and Boucher – focusing on the female form. ‘I had wrung Impressionism dry. I finally came to the conclusion that

I knew neither how to paint nor draw.’ He began a series of major figure paintings, in more linear style, the culmination being the monumental Les Grandes Baigneuses (1884-87) – ‘the loveliest nudes ever painted’ (Matisse) – in which he wanted to ‘beat Raphael’. But then, in 1888, Renoir changed direction once more, proclaiming that ‘I have taken up again, never to abandon it, my old style, soft and light of touch.’ And he went back to his previous colour and vibrance, to bourgeois scenes, the simple joy of pretty girls, bathers. Kenneth Clark referred to the ‘warm reality’ of his nudes. Today, some see them as ‘problematical’. But he was not a dirty old man. He merely relished the physical. ‘I like a painting which makes me want to stroll in it, if it is a landscape, or to stroke a breast or back, if it is a figure.’

From around 1903, he became increasingly arthritic, and had to tie a paintbrush to his crippled hand. His later paintings are too sweet for some,

From around 1903, he became increasingly arthritic, and had to tie a paintbrush to his crippled hand. His later paintings are too sweet for some,

too exaggerated for others (Mary Cassatt described his late bathers as ‘enormously fat red women with very small heads’). Nevertheless, they were admired by Picasso, Matisse and the sculptor Maillol (Renoir also turned to sculpture in his last years). Just before his death in 1919, Renoir saw his 1887 Portrait of Madame Georges Charpentier hung in the Louvre. He had joined

the pantheon of masters.