ALFRED HITCHCOCK (1899-1980), Master of Suspense

Hitchcock knew how to manipulate: ‘I enjoy playing the audience like a piano,’ he admitted. ‘There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it…’ He recognised that ‘everybody likes to be scared. Nothing has changed since Little Red Riding Hood faced the Big Bad Wolf.’ And he knew how to scare. Through anticipation, tension. And through the unexpected, as in Psycho (1960), perhaps his most original film. Rope (1948), made in 10-minute takes (the amount of film in a camera) is another candidate (although he dismissed it as ‘a stunt’); as is the peeping Tom Rear Window (1954), also a single set. Psycho displays his trademarks: the use of montage to suggest violence; unpredictable characters; cross-tracking; the camera as voyeur. And it includes the ‘MacGuffin’ (as he called it), an object or device which drives the plot. In Psycho it’s the envelope of $40,000 which Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals so she can be with her lover. Notable ‘MacGuffins’ include keys (Notorious, 1946; Dial M for Murder, 1954) and a wedding ring (Rear Window). Psycho, (like The Birds, 1963), has a long, taut opening allowing us to identify with our wayward heroine as she drives to Bates Motel. Unlike The Birds it has music – by his favourite composer, Bernard Herrmann. At the motel she meets the enigmatic owner Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and – 47 minutes into the film – takes a shower. Mistake. She is stabbed to death, a sequence (45 seconds, 78 camera setups) only possible in black and white, which Hitch used for economy, as it was partly self-financed. Colour would have been disgusting (in fact, Paramount rejected the script because they found it ‘too repulsive’). The horror is twofold: she is naked and vulnerable; and it is wholly unexpected. Janet Leigh is the star; directors do not kill their star in the second reel, with over an hour to go. But then there is another shock. A private eye (Martin Balsam) arrives to investigate Marion’s disappearance. He is our new hero, all is well. But then he too is killed! Blimey. Hitchcock toyed with convention: the secret of Vertigo (1958), voted by Sight & Sound as the greatest of all movies, is revealed two-thirds of the way through.

Hitchcock knew how to manipulate: ‘I enjoy playing the audience like a piano,’ he admitted. ‘There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it…’ He recognised that ‘everybody likes to be scared. Nothing has changed since Little Red Riding Hood faced the Big Bad Wolf.’ And he knew how to scare. Through anticipation, tension. And through the unexpected, as in Psycho (1960), perhaps his most original film. Rope (1948), made in 10-minute takes (the amount of film in a camera) is another candidate (although he dismissed it as ‘a stunt’); as is the peeping Tom Rear Window (1954), also a single set. Psycho displays his trademarks: the use of montage to suggest violence; unpredictable characters; cross-tracking; the camera as voyeur. And it includes the ‘MacGuffin’ (as he called it), an object or device which drives the plot. In Psycho it’s the envelope of $40,000 which Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals so she can be with her lover. Notable ‘MacGuffins’ include keys (Notorious, 1946; Dial M for Murder, 1954) and a wedding ring (Rear Window). Psycho, (like The Birds, 1963), has a long, taut opening allowing us to identify with our wayward heroine as she drives to Bates Motel. Unlike The Birds it has music – by his favourite composer, Bernard Herrmann. At the motel she meets the enigmatic owner Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and – 47 minutes into the film – takes a shower. Mistake. She is stabbed to death, a sequence (45 seconds, 78 camera setups) only possible in black and white, which Hitch used for economy, as it was partly self-financed. Colour would have been disgusting (in fact, Paramount rejected the script because they found it ‘too repulsive’). The horror is twofold: she is naked and vulnerable; and it is wholly unexpected. Janet Leigh is the star; directors do not kill their star in the second reel, with over an hour to go. But then there is another shock. A private eye (Martin Balsam) arrives to investigate Marion’s disappearance. He is our new hero, all is well. But then he too is killed! Blimey. Hitchcock toyed with convention: the secret of Vertigo (1958), voted by Sight & Sound as the greatest of all movies, is revealed two-thirds of the way through.

ACTORS – ‘A NECESSARY EVIL’

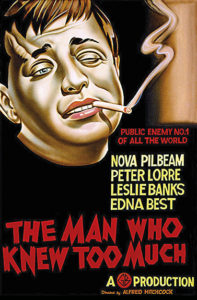

Alfred Joseph Hitchcock was born in Essex, son of a grocer and educated by Jesuits. Through childhood traumas he had lifelong aversions to policemen and eggs. In 1919 he joined a subsidiary of Paramount as a title card designer, where he met his future wife (and collaborator), the screenwriter Alma Reville. He took to directing when a director fell ill. His first trademark film was a silent Jack the Ripper thriller – The Lodger (1927). It features that Hitchcock obsession, mistaken identity. And another, the ice blonde. Hitchcock’s misogyny is debated, but of his stable of blondes – like Grace Kelly, Eva Marie Saint and Tippi Hedren – only Hedren (The Birds, 1963; Marnie, 1964) suffered, particularly from the beaks of the extras, the birds. One studio wanted him to use Monroe. ‘She didn’t appeal, too obvious, there is no mystery in the sex.’ He certainly wouldn’t have enjoyed her Method approach. ‘When an actor wants to discuss their motivation, I say, your salary.’ ‘Actors should be treated like cattle’ he famously said. ‘A necessary evil’ he called them.

Alfred Joseph Hitchcock was born in Essex, son of a grocer and educated by Jesuits. Through childhood traumas he had lifelong aversions to policemen and eggs. In 1919 he joined a subsidiary of Paramount as a title card designer, where he met his future wife (and collaborator), the screenwriter Alma Reville. He took to directing when a director fell ill. His first trademark film was a silent Jack the Ripper thriller – The Lodger (1927). It features that Hitchcock obsession, mistaken identity. And another, the ice blonde. Hitchcock’s misogyny is debated, but of his stable of blondes – like Grace Kelly, Eva Marie Saint and Tippi Hedren – only Hedren (The Birds, 1963; Marnie, 1964) suffered, particularly from the beaks of the extras, the birds. One studio wanted him to use Monroe. ‘She didn’t appeal, too obvious, there is no mystery in the sex.’ He certainly wouldn’t have enjoyed her Method approach. ‘When an actor wants to discuss their motivation, I say, your salary.’ ‘Actors should be treated like cattle’ he famously said. ‘A necessary evil’ he called them.

CARY GRANT

But Cary Grant was different. Hitch ‘loved’ Grant. He lured him out of retirement to make To Catch a Thief (1955) with Kelly, a film with all the hallmarks of classic Hitchcock. Beautiful actors and location (the Riviera), charming villain (Grant), a witty script (‘To make a great film you need three things – the script, the script and the script’). His baddies are always nuanced. ‘I’ve never been interested in professional criminals. The audience can’t identify with their lack of feeling.’ His films never end with a whimper: in Rebecca (1940) – Hitchcock’s first US film – the whole set, Manderley, goes up in smoke. North by Northwest (1959) climaxes on Mount Rushmore. The scene when Cary Grant is attacked by a crop-duster plane in a sun-baked Indiana prairie is a masterpiece of agoraphobia. The movie was a genre Hitch did best – the romantic comedy thriller. He did it triumphantly with The Lady Vanishes (1938) which led to his US contract from David O Selznick (his agent’s brother). Hitch has a droll cameo in that film and every one thereafter. It’s his way of pricking pretension. ‘It’s only a movie,’ he would say. ‘And we’re grossly overpaid.’ He laughed at his limitations. ‘I am a typed director… If I made Cinderella the audience would immediately be looking for a body in the coach.’