‘Fifteen men on the Dead Man’s Chest / Drink and the devil had done for the rest…’

‘Fifteen men on the Dead Man’s Chest / Drink and the devil had done for the rest…’

Treasure Island, R.L. Stevenson’s story (1883) of peglegs, parrots and buried gold has immortalised (and glamourised) the cutthroat world of piracy on the Spanish Main. Some things are just fiction, like ‘walking the plank’ – as Captain Hook (an Etonian gone wrong) did in Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904). Yet the camaraderie of these outcasts is true; they were a collective, a sort of trade union of baddies. But woe betide the scab. Here is a lexicon of piracy:

PIRATES were sea-going gangsters according to their victims, swashbuckling heroes according to Hollywood. Anyone who attacks and robs a ship at sea is a pirate.

A BUCCANEER is, specifically, a pirate rampaging in the Caribbean during the late 17C and early 18C, a freebooter mostly preying on Spanish ships and settlements.

A PRIVATEER is a licenced pirate, the most notorious (and successful) being Sir Francis Drake and his Golden Hind. They were paramilitary private contractors, granted rights to raid enemy ships and keep a cut of the spoils. They provided their own ship and crew.

A CORSAIR was a French privateer but became a romantic name for all pirates or privateers. The most famous was Robert Surcouf of St Malo; a naughty pirate, he broke his contract when he raided French ships as well as the enemy’s.

FAMOUS PIRATES

The classic era of piracy in the Caribbean lasted from around 1650-1730. By 1650, France, England and the Dutch began to develop their colonial empires. Valuable, tempting cargoes travelled by ship. Bartholomew Roberts, a Welshman also known as Black Bart, was the pirate with most prizes (400!) during this Golden Age. A nasty piece of work, he hanged the governor of Martinique from the yardarm of his ship. Blackbeard, the Englishman Edward Teach, created a fleet of pirates. He was CEO of a mighty conglomerate; his flagship alone, Queen Anne’s Revenge, having 40 guns and 300 crew – intemperate tars with a liking for liquor (‘Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!’), needing careful man-management. Mr Teach lit fuses under his hat to frighten his enemies, creating a brand identity. His logo was a white skull on a black flag. The Jolly Roger (skull and crossbones) was first flown by French pirate Emanuel Wynn; one with crossed sabres was the trademark of English pirate Calico Jack (John Rackham), famous for his women crew members, Mary Read and his lover, Anne Bonny. Blackbeard ended up with his head on a bowsprit; Jack was hanged. They should have retired like Long Ben (Henry Every) who once captured a Mogul horde worth £100m today! Good business. Buccaneers were surprisingly democratic: the captain was elected. Crews decided whether to attack a ship. They were paid only from plunder (‘no prey, no pay’) which was divided into shares. A doctor was third in line on a privateer; on most pirate ships, the ‘doctor’ was the cook or carpenter, men with the tools for amputation.

A boost to piracy was the ending in 1714 of the War of the Spanish Succession. Thousands of seamen were now idle and broke when the transatlantic colonial trade was booming. The merchant navy was a poor option. An excess of labour drove wages down (pay was even worse in the Royal Navy) and greedy owners overloaded vessels. Mortality rates were as high as slave ships’.

HOLLYWOOD

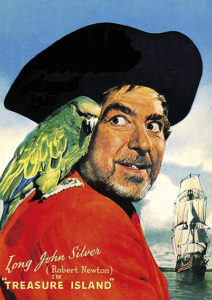

Hollywood discovered the allure of pirate pictures early. Treasure Island (1912) was later made with Robert Newton as Long John Silver (1950) – he it was who invented the pirate patois, Newton’s own (if exaggerated) West Country burr – ‘Arrrr…Jim Lad!’ Etc. Two films starring Errol Flynn, Captain Blood (1935) and The Sea Hawk (1940), proved Flynn the pirate of your dreams – gallant, romantic and a hell of a swordsman. Pirate movies offered escapism on the briny, plus violence and sex. Costumes were skimpy – Jean Peters (briefly Mrs Howard Hughes), called her outfit in Anne of the Indies (1951) ‘tight-fitting rags’. Burt Lancaster’s rugged chest was the star of The Crimson Pirate(1952). But it is Flynn who is remembered. Bette Davis scorned his acting, yet he could shout ‘ALL RIGHT ME HEARTIES! FOLLOW ME!’ without giggling, such was his simple sincerity. Studios liked pirate movies; the public were not too fussed about verisimilitude. In Captain Blood (‘TERROR of the CARIBBEAN!’) California stood in for the Caribbean and sea battles were either footage from the 1924 Sea Hawk, or performed by miniatures. Korngold’s brilliant score, composed in a hectic three weeks, was in part nicked from Liszt. Pirate props and ingredients are the same: rigging, sails, a wind machine, bangs, a few cheap accessories like earrings (worn by real pirates to ease sea sickness by applying pressure to ear lobes) … and a ferocious duel with love triumphant. The Pirates of the Caribbean franchise proves that the formula of rum, rapiers and rumpy-pumpy sells…

Hollywood discovered the allure of pirate pictures early. Treasure Island (1912) was later made with Robert Newton as Long John Silver (1950) – he it was who invented the pirate patois, Newton’s own (if exaggerated) West Country burr – ‘Arrrr…Jim Lad!’ Etc. Two films starring Errol Flynn, Captain Blood (1935) and The Sea Hawk (1940), proved Flynn the pirate of your dreams – gallant, romantic and a hell of a swordsman. Pirate movies offered escapism on the briny, plus violence and sex. Costumes were skimpy – Jean Peters (briefly Mrs Howard Hughes), called her outfit in Anne of the Indies (1951) ‘tight-fitting rags’. Burt Lancaster’s rugged chest was the star of The Crimson Pirate(1952). But it is Flynn who is remembered. Bette Davis scorned his acting, yet he could shout ‘ALL RIGHT ME HEARTIES! FOLLOW ME!’ without giggling, such was his simple sincerity. Studios liked pirate movies; the public were not too fussed about verisimilitude. In Captain Blood (‘TERROR of the CARIBBEAN!’) California stood in for the Caribbean and sea battles were either footage from the 1924 Sea Hawk, or performed by miniatures. Korngold’s brilliant score, composed in a hectic three weeks, was in part nicked from Liszt. Pirate props and ingredients are the same: rigging, sails, a wind machine, bangs, a few cheap accessories like earrings (worn by real pirates to ease sea sickness by applying pressure to ear lobes) … and a ferocious duel with love triumphant. The Pirates of the Caribbean franchise proves that the formula of rum, rapiers and rumpy-pumpy sells…