FOREVER WILD

The National Parks of America

‘Here in the United States we turn our rivers and streams into sewers and dumping-grounds, we pollute the air, we destroy forests, and exterminate fishes, birds and mammals…we are prone to speak of the resources of this country as inexhaustible; this is not so.’

TEDDY ROOSEVELT

The great hero of American conservationism is Theodore Roosevelt, who became President in 1901, following the shooting and death of President McKinley. President Roosevelt extended protection of wildlife and wilderness by establishing the U.S. Forest Service (1905) and 51 Federal Bird Reservations, 4 National Game Preserves and 150 National Forests. Through the 1906 American Antiquities Act he proclaimed 18 National Monuments. He also established 5 National Parks. In all he protected about 230m acres of public land. Roosevelt lauded the ‘wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the great loneliness and beauty’ of nature. ‘Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.’ The US has 59 national parks (managed by the National Park Service since 1916), of which the first was Yellowstone (1872). Sequoia and Yosemite followed in 1890, and the Adirondack Park in 1892. Teddy Roosevelt heard that McKinley was dying via a telegram delivered on top of Mt Marcy, the highest peak in the Adirondacks in New York State. Its preservation, like that of many a wilderness, is due to the foresight and lobbying of prescient people. In the 19th century rich families from Boston, New York and Philadelphia summered in the Adirondacks (like the artist Winslow Homer) to enjoy the lakes and streams and mountains, no doubt inspired by Thoreau’s Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings; and at one with Roosevelt’s assertion that – ‘The farther one gets into the wilderness, the greater is the attraction of its lonely freedom.’

The great hero of American conservationism is Theodore Roosevelt, who became President in 1901, following the shooting and death of President McKinley. President Roosevelt extended protection of wildlife and wilderness by establishing the U.S. Forest Service (1905) and 51 Federal Bird Reservations, 4 National Game Preserves and 150 National Forests. Through the 1906 American Antiquities Act he proclaimed 18 National Monuments. He also established 5 National Parks. In all he protected about 230m acres of public land. Roosevelt lauded the ‘wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the great loneliness and beauty’ of nature. ‘Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.’ The US has 59 national parks (managed by the National Park Service since 1916), of which the first was Yellowstone (1872). Sequoia and Yosemite followed in 1890, and the Adirondack Park in 1892. Teddy Roosevelt heard that McKinley was dying via a telegram delivered on top of Mt Marcy, the highest peak in the Adirondacks in New York State. Its preservation, like that of many a wilderness, is due to the foresight and lobbying of prescient people. In the 19th century rich families from Boston, New York and Philadelphia summered in the Adirondacks (like the artist Winslow Homer) to enjoy the lakes and streams and mountains, no doubt inspired by Thoreau’s Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings; and at one with Roosevelt’s assertion that – ‘The farther one gets into the wilderness, the greater is the attraction of its lonely freedom.’

ADIRONDACKS

While making the first ascent of Seward Mountain (1870), a New York lawyer, Verplanck Colvin (1847-1920), noted with horror the damage done by lumbermen. He alerted the state government, arguing that without trees and roots, the mountainous slopes would erode, and the Erie Canal and even Hudson River could silt up, choking off New York’s economic spine. Action was taken. This lesser known great park covers over 6m acres, roughly the area of Vermont, and greater than the National Parks of Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Glacier and Great Smoky Mountains combined.

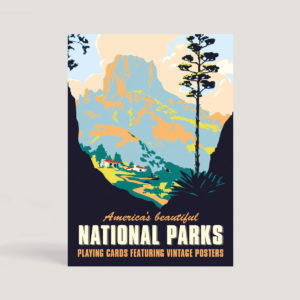

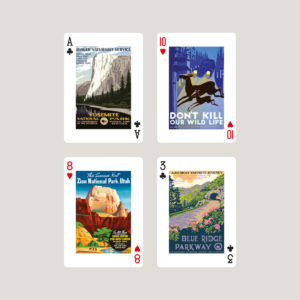

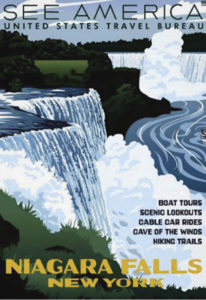

THE WPA AND THE FEDERAL ART PROJECT

The Works Progress Administration was the largest of Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies, employing millions of mostly unskilled men to carry out construction projects, like building roads, bridges and schools. Between 1935 and 1943 (when it was wound up due to low unemployment generated by WW2) the WPA provided almost 8m jobs and spent a staggering $13.4 billion. The WPA was not universally popular. Some Republicans thought it mere ‘socialism’ and profligate to boot, and that foremen and workers idled on a job to prolong employment. A Senate committee agreed that ‘poor work habits are not remedied’. In Harper Lee’s 1960 novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, Bob Ewell, the lazybones of Maycomb County, is described as ‘the only person fired from the WPA for laziness.’ Only a very small proportion of the budget was spent by the Federal Art Project. It employed writers, musicians and actors. Poster artists were commissioned to promote education, health, music, drama, safety, travel and art. Although some of its advertising was irritatingly nannyish – ‘Avoid Accidents’, ‘Keep Your Teeth Clean’, ‘Eat Your Vegetables’ – the Project’s eye-catching posters are the WPA’s lasting legacy. The FAP printed over 2m posters in 35,000 different designs, the most famous being those that promoted tourism in the National Parks, which make up the core of this deck. Their trademark was clarity and simplicity. They are bold, sharply outlined and use the solid colours favoured by the great German poster artist Ludwig Hohlwein (1874-1949), who clearly inspired these, mostly unknown, American artists. A technical innovation was the use (from 1936) of silkscreen, previously only a commercial medium. Many FAP posters are jewels of graphic art, and monuments to what can be achieved by imaginative public patronage. They best evoke, in pictures, Teddy Roosevelt’s vision of America because – ‘There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy, and its charm.’

The Works Progress Administration was the largest of Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies, employing millions of mostly unskilled men to carry out construction projects, like building roads, bridges and schools. Between 1935 and 1943 (when it was wound up due to low unemployment generated by WW2) the WPA provided almost 8m jobs and spent a staggering $13.4 billion. The WPA was not universally popular. Some Republicans thought it mere ‘socialism’ and profligate to boot, and that foremen and workers idled on a job to prolong employment. A Senate committee agreed that ‘poor work habits are not remedied’. In Harper Lee’s 1960 novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, Bob Ewell, the lazybones of Maycomb County, is described as ‘the only person fired from the WPA for laziness.’ Only a very small proportion of the budget was spent by the Federal Art Project. It employed writers, musicians and actors. Poster artists were commissioned to promote education, health, music, drama, safety, travel and art. Although some of its advertising was irritatingly nannyish – ‘Avoid Accidents’, ‘Keep Your Teeth Clean’, ‘Eat Your Vegetables’ – the Project’s eye-catching posters are the WPA’s lasting legacy. The FAP printed over 2m posters in 35,000 different designs, the most famous being those that promoted tourism in the National Parks, which make up the core of this deck. Their trademark was clarity and simplicity. They are bold, sharply outlined and use the solid colours favoured by the great German poster artist Ludwig Hohlwein (1874-1949), who clearly inspired these, mostly unknown, American artists. A technical innovation was the use (from 1936) of silkscreen, previously only a commercial medium. Many FAP posters are jewels of graphic art, and monuments to what can be achieved by imaginative public patronage. They best evoke, in pictures, Teddy Roosevelt’s vision of America because – ‘There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy, and its charm.’