BRITAIN’S ‘FINEST HOUR’

IN 1940, with France defeated, Hitler’s planned invasion of Britain [Operation Sealion] was launched on July 16 with sorties against Channel shipping and ports. Three days later Hitler offered peace, but Churchill stiffened his Cabinet’s resolve to fight on. On August 13 Goering, the Luftwaffe commander, switched attacks and launched Adlertag (Eagle Day) against RAF airfields and radar stations. The RAF was losing planes, but more importantly experienced pilots (25% of RAF pilots were lost in two weeks). Just as the RAF’s resistance was fully stretched Goering made a fatal mistake.

BLITZ

On September 7, after a brief lull, he spared the airfields and bombed London, initially a retaliatory raid for RAF bombs falling on Berlin. The Blitz had begun. For the next 57 nights Britain’s cities were pounded in a vain attempt to break Britain’s will to fight. London’s East End bore the brunt. Churchill toured the ruins, something Hitler never did in Berlin. If morale wobbled, there was a general cussed determination to ensure ‘business as usual’. The Royal Family remained in London. Buckingham Palace was hit, prompting the Queen to say ‘now I can look the East End in the face.’ The government thought that providing deep shelters would encourage malingering but reversed the policy when Londoners stayed in tube stations overnight. Posters urged the eating of carrots because they ‘help you see in the blackout’. They didn’t. Rationing was necessary but grim. One egg a week, unlimited Spam but that soon palled. Churchill looked at the allowance and commented ‘a good meal’ – he was looking at a week’s ration!

On September 7, after a brief lull, he spared the airfields and bombed London, initially a retaliatory raid for RAF bombs falling on Berlin. The Blitz had begun. For the next 57 nights Britain’s cities were pounded in a vain attempt to break Britain’s will to fight. London’s East End bore the brunt. Churchill toured the ruins, something Hitler never did in Berlin. If morale wobbled, there was a general cussed determination to ensure ‘business as usual’. The Royal Family remained in London. Buckingham Palace was hit, prompting the Queen to say ‘now I can look the East End in the face.’ The government thought that providing deep shelters would encourage malingering but reversed the policy when Londoners stayed in tube stations overnight. Posters urged the eating of carrots because they ‘help you see in the blackout’. They didn’t. Rationing was necessary but grim. One egg a week, unlimited Spam but that soon palled. Churchill looked at the allowance and commented ‘a good meal’ – he was looking at a week’s ration!

CASUALTIES

An attack on September 15 – Battle of Britain Day – led to heavy Luftwaffe losses (60 aircraft, not the 185 claimed, in exchange for 26 RAF fighters). Hitler ordered the indefinite postponement of Sealion on October 12, but the Blitz continued with attacks in October on Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester; and on November 14 a devastating raid on Coventry, which has led to the myth that Churchill allowed the city to be destroyed to keep ‘Ultra’, the decoding of German signals traffic, secret. In January Bristol, Cardiff and Portsmouth were hit. The Blitz (officially) ended in May 1941 but sporadic raids continued until the onslaught of Hitler’s pilotless terror weapons in 1944 – the V1 ‘Doodlebug’ or ‘Buzz Bomb’, and the V2 rocket which exploded without warning. Britain lost 60,000 civilian dead from air attack, compared to Germany’s civilian death toll of 2 million or more.

PILOTS AND PLANES

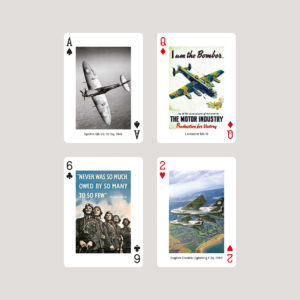

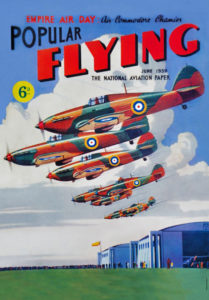

The Battle of Britain was won by her pilots, ground crews and their commander, Air Marshal ‘Stuffy’ Dowding. He had pressed upon Churchill the folly of sending yet more fighter squadrons to prop up an already doomed France, had built Britain’s crucial early warning radar system, and with Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park of 11 Group (in the Battle’s maelstrom), had perfected tactics that ensured the speedy interception and destruction of raiders. That the sturdy, nimble single-seat Hurricane, and the faster Spitfire, were available was due in part to Dowding’s drive. They were a match for the Luftwaffe’s ME 109, despite being undergunned, although the latter’s excellence, and the skill of German pilots, is illustrated by their top ace Helmut Wick’s 42 kills against the 17 of Allied top ace Sgt. J. Frantisek, a Czech of Polish 303 Sq. The Poles and Czechs outscored British pilots, despite their late deployment due to Dowding’s unfounded suspicion about their discipline. Churchill paid tribute to the RAF’s young, brave pilots in the House of Commons on August 20 – ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’ It was Britain’s ‘finest hour’.

The Battle of Britain was won by her pilots, ground crews and their commander, Air Marshal ‘Stuffy’ Dowding. He had pressed upon Churchill the folly of sending yet more fighter squadrons to prop up an already doomed France, had built Britain’s crucial early warning radar system, and with Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park of 11 Group (in the Battle’s maelstrom), had perfected tactics that ensured the speedy interception and destruction of raiders. That the sturdy, nimble single-seat Hurricane, and the faster Spitfire, were available was due in part to Dowding’s drive. They were a match for the Luftwaffe’s ME 109, despite being undergunned, although the latter’s excellence, and the skill of German pilots, is illustrated by their top ace Helmut Wick’s 42 kills against the 17 of Allied top ace Sgt. J. Frantisek, a Czech of Polish 303 Sq. The Poles and Czechs outscored British pilots, despite their late deployment due to Dowding’s unfounded suspicion about their discipline. Churchill paid tribute to the RAF’s young, brave pilots in the House of Commons on August 20 – ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’ It was Britain’s ‘finest hour’.