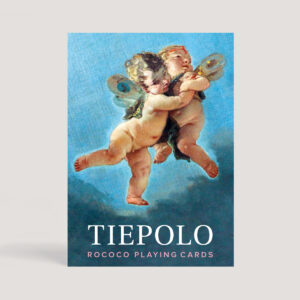

‘A painter’s mind must always aim at the sublime, the heroic and for perfection.’ So said Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770). He is the master of the Grand Manner. He may have lived in the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, but his art is pure theatre. There is nothing rational about it, nothing worldly. His paintings are poetic masterpieces of colour: sensual, magical. Caravaggio’s martyr or saint looks like the bloke next door; Tiepolo gives him the majesty of the heavens. His frescoed ceilings soar – away from earthly squalor. In our age Tiepolo has been neglected, because he is too decorative and too much the servant of noble and royal patrons. He has been described as ‘the last breath of happiness in Europe’, who perhaps sits uneasily in our age of cynicism. But to regard his art as mere Rococo frippery is to misunderstand its purpose, and its personal nature. With his triumphant ceilings he is in the entertainment business. He wants to please his patron and wow the public. His altarpieces, pious but exuberant, are designed to uplift. His themes are not just Madonnas or cherubs but something more personal – they convey his feelings about naked bodies or the chubbiness of babies, the dogginess of dogs or his dreams of flying.

‘A painter’s mind must always aim at the sublime, the heroic and for perfection.’ So said Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770). He is the master of the Grand Manner. He may have lived in the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, but his art is pure theatre. There is nothing rational about it, nothing worldly. His paintings are poetic masterpieces of colour: sensual, magical. Caravaggio’s martyr or saint looks like the bloke next door; Tiepolo gives him the majesty of the heavens. His frescoed ceilings soar – away from earthly squalor. In our age Tiepolo has been neglected, because he is too decorative and too much the servant of noble and royal patrons. He has been described as ‘the last breath of happiness in Europe’, who perhaps sits uneasily in our age of cynicism. But to regard his art as mere Rococo frippery is to misunderstand its purpose, and its personal nature. With his triumphant ceilings he is in the entertainment business. He wants to please his patron and wow the public. His altarpieces, pious but exuberant, are designed to uplift. His themes are not just Madonnas or cherubs but something more personal – they convey his feelings about naked bodies or the chubbiness of babies, the dogginess of dogs or his dreams of flying.

Tiepolo was born and trained in Venice, his precocity revealed by dazzling draughtsmanship. His exuberant invention and virtuoso handling of paint is unmistakably Venetian. Tiepolo was influenced by Piazzetta and Ricci, but the colouring and, above all, the movement of his compositions, derive from Veronese. Unlike the petulant Piazzetta and grumpy (and ‘exorbitant’) Canaletto, Tiepolo was (a contemporary noted) ‘a happy painter by nature’ even if his imagination was ‘all spirit and fire’. Bidding and benign, he travelled widely to fulfil the extravagant demands of princes. He moved in 1750 with his artist sons to Würzburg to decorate the residence of the Prince-Bishop, his greatest achievement. Over the grandiose staircase, Tiepolo painted a vast ceiling showing Apollo and the continents, opening onto a brilliant sky filled with Olympian gods. Tiepolo used multiple viewpoints, because the ceiling would be seen at different angles during the ceremonial progress of visitors climbing the stairs. Tiepolo’s capriccios, his fantasies, may have been a sort of immersive staged fiction, like opera (he even used a perspective designer), but he was acutely aware of site and function.

Yet Tiepolo played with effects, often with wit. In his Adoration of the Magi (1753) a king wears a turban. It is a cartoon turban. A whopper. Absurd, yet it serves a purpose. It is both a focal point and the very essence of the exotic Orient. But in later life, when he went to Spain (1762), he had a conversion. His painting becomes serene. He abandons high drama and tells a story quietly. He returns to an earlier subject, The Flight into Egypt. There are no pyrotechnics, no flapping angels, just a tired family, tired donkey, in an asymmetrical landscape against a muted sky. He was a bravura artist who, with all his flourishes, knew the value of silence. Tiepolo was the last hurrah of the ancien regime before Venice itself was given over to the picturesque, and the tourist.