RAPHAEL (1483-1520), so his biographer Vasari tells us, died aged only 37 of too much sex. This unlikely scenario does however tell us something about the man. He was passionate. He was beguiling. The coquettish woman in La Fornarina (his mistress?) holds a bare breast while pointing at an armband bearing his name, as if she belonged to Raphael. Her sidelong eyes seem to share a joke.

RAPHAEL (1483-1520), so his biographer Vasari tells us, died aged only 37 of too much sex. This unlikely scenario does however tell us something about the man. He was passionate. He was beguiling. The coquettish woman in La Fornarina (his mistress?) holds a bare breast while pointing at an armband bearing his name, as if she belonged to Raphael. Her sidelong eyes seem to share a joke.

Unlike his tormented rivals, Michelangelo and Leonardo, he had no repressed or unrepressed anger. And his sublime nature is reflected in the serenity of his painting, particularly his ‘dear Madonnas’, as Robert Browning called them. The Marquis de Sade said the Madonna della Seggiola could convert an atheist. It became the focus of many a Grand Tour. A ‘waiting list’ was created: smart young Englishmen booked their slot to see or draw the Madonna.

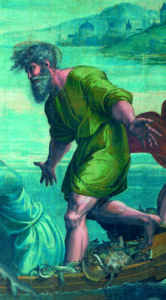

Raphael strove for perfection, perfection of grace and line. Even agony is immaculate. St. Catherine of Alexandria poses exquisitely, modelling martyrdom with her wheel – emblem of her torture – as an accessory. St. George smites the dragon with languid ease, in fashionable gleaming armour. St. Michael lands balletically upon Lucifer. Whacking evil is stylish and elegant. Raphael is an old master out of shape with our time, which prefers genius troubled.

Raphael was not distracted by science, as Leonardo was (‘Leonardo fretted his life away in engineering’ – Ruskin). He was a painter. He did not crave the sculptor’s chisel like Michelangelo, although his fascination with classical proportion (particularly of the Pantheon) steered him to architecture. He was appointed chief architect of St Peter’s by Pope Leo X in 1514 and a year later supervisor of Roman antiquities and excavations.

Born in Urbino, orphaned at 11, the prodigy was a master painter at 17. He left his hilltop birthplace for Perugia, and the workshop of Perugino; then moved to Florence, where he absorbed Leonardo’s smoky technique (sfumato). In Rome, by now successful, he worked for two popes and their Vatican bankers and managed a sneak preview of Michelangelo’s progress in the Sistine Chapel, which gave muscularity and torque to his poses.

In his short life his output was prodigious, the product of Raphael’s inspiration and his studio’s perspiration: cartoons for the Sistine tapestries, designs for St Peter’s, the Vatican Stanze – immense murals that tourists bypass on their way to Michelangelo – the frescoes at Villa Farnesina, the Madonnas, the altarpieces… How did he find time for sex?

Raphael’s women are sublime; if in their perfection they have none of Ruben’s or Renoir’s tactile allure they are still women, modelled from women, not men with breasts like Michelangelo’s women. And for every idealised Madonna, there is a real mother cradling and protecting a real child. Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo, with its squirming baby, inspired Raphael to depict similar intimacy, something natural and spontaneous, the sort of closeness that Donatello strove for.

Vasari called Raphael a ‘mortal god’. But Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites rejected Raphael because he followed the ideas of Alberti, the father of art theory, who believed in objective rules of harmony (based on antiquity) and on the primacy of beauty over realism. Beauty was ‘the adjustment of all parts proportionately’. Ruskin thought Raphael contrived and ‘untrue’. Raphael explained his idealism thus: ‘to paint a beautiful woman, I would have to see several beautiful women… but because there are so few, I make use of a certain idea…’

When Raphael died his last unfinished work, The Transfiguration (‘glorious, lovely, divine’ – Vasari) was carried at his funeral procession. It is a miraculous composition, wholly lost on Ruskin who commented crassly: ‘everybody seemed to be pointing at everybody else, and nobody, to my notion, was worth pointing at.’ Christ floats in majesty. Only Titian and Tiepolo manage this ethereal alchemy so brilliantly. In another altarpiece, the Sistine Madonna, the Virgin wafts on a cloud, holding the Christ Child. They stare outwards, with expressions of pain and dejection and resignation. Because, in the church in Piacenza where the painting hung, they stared at a Crucifixion. But in this reverential scene Raphael has added an extraordinary human touch. Two little putti, little angels, look up at the Madonna, elbows on a ledge. Are they transfixed with piety, with awe? No, they are bored witless. The story goes that they were the children of the model who posed for the Virgin. Mum couldn’t get a babysitter so she brought them to the studio. Now they are immortalised in a million fridge magnets.

When Raphael died his last unfinished work, The Transfiguration (‘glorious, lovely, divine’ – Vasari) was carried at his funeral procession. It is a miraculous composition, wholly lost on Ruskin who commented crassly: ‘everybody seemed to be pointing at everybody else, and nobody, to my notion, was worth pointing at.’ Christ floats in majesty. Only Titian and Tiepolo manage this ethereal alchemy so brilliantly. In another altarpiece, the Sistine Madonna, the Virgin wafts on a cloud, holding the Christ Child. They stare outwards, with expressions of pain and dejection and resignation. Because, in the church in Piacenza where the painting hung, they stared at a Crucifixion. But in this reverential scene Raphael has added an extraordinary human touch. Two little putti, little angels, look up at the Madonna, elbows on a ledge. Are they transfixed with piety, with awe? No, they are bored witless. The story goes that they were the children of the model who posed for the Virgin. Mum couldn’t get a babysitter so she brought them to the studio. Now they are immortalised in a million fridge magnets.