MICHELANGELO was 17 when a fellow student (‘a bestial and arrogant man’) punched him on the nose and broke it. It was a permanent disfigurement that this celebrant of male beauty felt keenly. Anger burned throughout his life. One papal patron, Leo X, dithered over commissioning the great artist: ‘But he is terribile; one cannot deal with him.’ Yet it was his terribilità, his ability to instil awe, terror or a sense of the sublime, that led contemporaries to call him Il Divino (‘the divine one’); and led artists to emulate his expressive physicality through Mannerism to Baroque and all the way to the 19C and Blake (Michelangelo was his ‘Outrageous Demon’), Géricault and beyond. Henry Moore was inspired to sculpt by Michelangelo and ‘the intimation that one man could feed the world’s spirit for ever’. Vasari, Michelangelo’s protégé and biographer, claimed he was the greatest artist ever because he was ‘supreme in not one art alone but in all three’ painting, sculpture and architecture. And he was a poet. But genius was, for Michelangelo, ‘perseverance’ and ‘if people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all.’

MICHELANGELO was 17 when a fellow student (‘a bestial and arrogant man’) punched him on the nose and broke it. It was a permanent disfigurement that this celebrant of male beauty felt keenly. Anger burned throughout his life. One papal patron, Leo X, dithered over commissioning the great artist: ‘But he is terribile; one cannot deal with him.’ Yet it was his terribilità, his ability to instil awe, terror or a sense of the sublime, that led contemporaries to call him Il Divino (‘the divine one’); and led artists to emulate his expressive physicality through Mannerism to Baroque and all the way to the 19C and Blake (Michelangelo was his ‘Outrageous Demon’), Géricault and beyond. Henry Moore was inspired to sculpt by Michelangelo and ‘the intimation that one man could feed the world’s spirit for ever’. Vasari, Michelangelo’s protégé and biographer, claimed he was the greatest artist ever because he was ‘supreme in not one art alone but in all three’ painting, sculpture and architecture. And he was a poet. But genius was, for Michelangelo, ‘perseverance’ and ‘if people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all.’

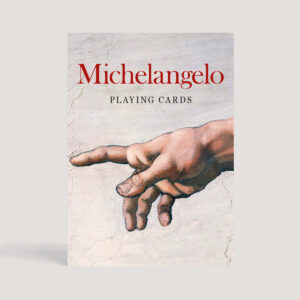

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564) was born in Caprese (now Caprese Michelangelo for the tourists) near Arezzo, but the family moved to Florence when he was a baby. His father was a failed banker. Age 13, Michelangelo was apprenticed to the prominent painter Ghirlandaio. Justa year later he was working for the Medici, de facto rulers of Florence, who ‘commissioned’ after a snowfall… a snowman (now lost). The Medici were not above fraud. Michelangelo sculpted a St. John the Baptist (1495-96) and was told ‘to make it look as if it’s been buried so it can be passed off as an ancient work and sold much better’. But the fraud was rumbled. The buyer, Cardinal Riario, was nevertheless dazzled by the work and asked the artist to come to Rome. So started Michelangelo’s long, tempestuous career in the city. His first major commission (1498, from the French ambassador) was for the great Pietà, now in St. Peter’s, a marble sculpture (attacked by a madman in 1972) of the Virgin grieving over the body of Christ. Vasari marvelled that ‘a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.’ Also impressed was Pope Julius II. He asked – or told – Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The theme of God’s relationship to man, of creation, damnation and salvation is realised in 300 bodies, sometimes naked, often dynamic. Michelangelo painted alone, in great discomfort. He had not wanted the job (his rival Bramante had proposed him, hoping he’d fail). He was a sculptor, he protested. He laboured long. The equally volatile Julius grew impatient. ‘When will you be finished?’ he shouted, whacking Michelangelo with his mace. ‘When I am done’ replied the artist. When it was ‘done’ (1512), Vasari noted that ‘everyone rushed to see it from every part and remained dumbfounded.’

ambassador) was for the great Pietà, now in St. Peter’s, a marble sculpture (attacked by a madman in 1972) of the Virgin grieving over the body of Christ. Vasari marvelled that ‘a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.’ Also impressed was Pope Julius II. He asked – or told – Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The theme of God’s relationship to man, of creation, damnation and salvation is realised in 300 bodies, sometimes naked, often dynamic. Michelangelo painted alone, in great discomfort. He had not wanted the job (his rival Bramante had proposed him, hoping he’d fail). He was a sculptor, he protested. He laboured long. The equally volatile Julius grew impatient. ‘When will you be finished?’ he shouted, whacking Michelangelo with his mace. ‘When I am done’ replied the artist. When it was ‘done’ (1512), Vasari noted that ‘everyone rushed to see it from every part and remained dumbfounded.’

30 years later, the violence and nakedness of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement (1536-41) on the altar wall sparked outrage and nearly led to the fresco’s destruction. This was the era of the Counter-Reformation, of the Inquisition. What future critics saw as the crowning of the ‘heroic’ style, was called a ‘voluptuous bathroom’. El Greco offered to produce something more ‘decent and pious’. In the end a chap painted over the naughty bits.

Michelangelo used the nude to express emotion. And in the colossal David (1501-04) we have, as one critic said, ‘the most perfect statue of a nude man, of life in marble.’ Michelangelo, in his words, ‘freed the figure from the stone’. It embodies a humanist ideal, where man is God’s finest creation. No less impressive is his Moses (1513-15), with its labyrinthine beard and gaze of wonder as God’s word is revealed. It was to be one of 40 statues for Julius II’s tomb, a project that evaporated. The intricacy of the hair, its delicacy, is that of a painter; as his painted nudes are those of a sculptor (‘Good painting is the kind that looks like sculpture’ he wrote). But always drawing is central. The Venetian (and colourist) Titian was fine, said Michelangelo, but would be better if he’d learnt to draw.

In old age he said – ‘I am still learning’. Vasari noted: ‘nothing he did satisfied him’. He destroyed much; but his vitality was prodigious. One witness observed him a week before his death ‘attacking the stone with such energy and fire I thought it would fly into pieces.’ If dismissive of rivals (‘What Raphael had of art, he had from me’) he yet revered the past, the ancients. His most visible monument is St. Peter’s dome. Against a clear sky it appears ‘an angelic and not human design’, as Michelangelo said of the Pantheon. Kenneth Clark called David – ‘One of the great events in the history of Western man.’ So is Michelangelo.

In old age he said – ‘I am still learning’. Vasari noted: ‘nothing he did satisfied him’. He destroyed much; but his vitality was prodigious. One witness observed him a week before his death ‘attacking the stone with such energy and fire I thought it would fly into pieces.’ If dismissive of rivals (‘What Raphael had of art, he had from me’) he yet revered the past, the ancients. His most visible monument is St. Peter’s dome. Against a clear sky it appears ‘an angelic and not human design’, as Michelangelo said of the Pantheon. Kenneth Clark called David – ‘One of the great events in the history of Western man.’ So is Michelangelo.